Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

The most alarming part of the email, for Pima County Recorder Gabriella Cázares-Kelly, was that it included the address of her office.

“Hello, I’ve planted a bomb (lead azide) in your office at 240 Stone Avenue,” the email began. “It is small and hidden very well.” Even before she was done reading, Cázares-Kelly picked up the phone on her desk and dialed 911.

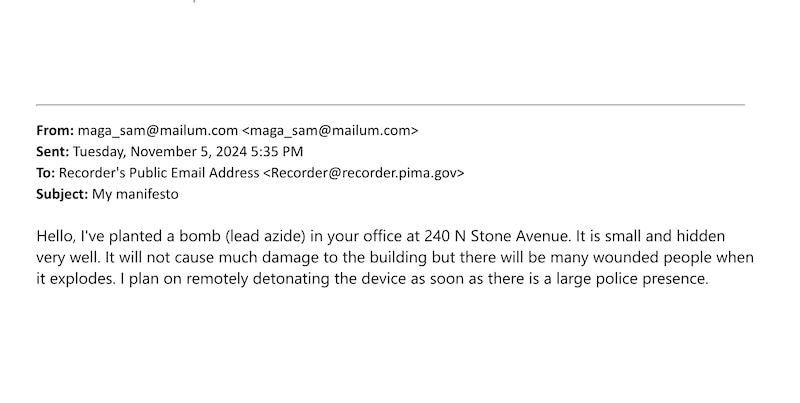

The contents of the email, which Votebeat obtained through a public records request, bring to light the nature of at least one of the hoax bomb threats that counties in Arizona and several other states received on Election Day. This one was sent from an email address mentioning “maga,” and threatened the bomb would lead to “many wounded people.” It appears to contain similar language — and be from a similar sender — to the one Cochise County officials received, according to a story by Herald/Review Media.

At the point Pima County officials received it, around 5:30 p.m. Nov. 5, the FBI had already put out a news release explaining that it was investigating similar threats in several states, but the agency had determined them to be noncredible. So Cázares-Kelly was not too worried. Still, she wanted to take precautions.

A bomb-sniffing dog was soon searching the building, she said, which also includes a courthouse and other county offices. Cázares-Kelly told staff they could leave if they were uncomfortable, she said, but law enforcement did not force them to evacuate. It was quickly determined there was no active threat.

“We were very aware that this was meant to cause disruption to the voting process, and, frankly, we have been prepared for this,” Cázares-Kelly said.

Threats are still under FBI investigation

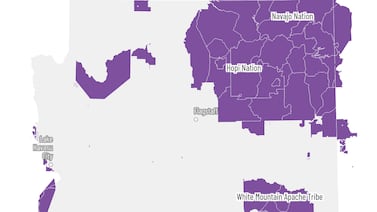

In all, election officials in 10 of Arizona’s 15 counties received hoax bomb threats, a spokesperson for Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes’ office confirmed. They were directed at election centers where ballots were being counted, polling places, or recorder’s offices in Coconino, Cochise, Gila, La Paz, Maricopa, Navajo, Pima, Pinal, Yavapai, and Yuma counties. The extent of the threats was first reported by AZ Mirror earlier this week.

Election officials across the state responded to the threats differently, according to media accounts from several counties. Some offices, in Cochise, La Paz, and Maricopa counties, evacuated. Others, such as in Pima County, did not. Police in many cases sent bomb-sniffing dogs through the buildings to ensure there was no threat.

The threats are still under investigation by the FBI, according to Mayes’ spokesperson. They appear to have Russian origins, the FBI said in its initial Nov. 5 statement. Asked on Friday if all the threats were connected, an FBI spokesperson declined to provide more information.

In response to a public records request, the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office refused this week to provide copies of any threat received by counties in the state and information about who sent them. But the Pima County Recorder’s Office provided the full email it received.

The subject was “My manifesto,” and the sender was maga_sam@mailum.com.

The sender wrote that the bomb wouldn’t cause much damage to the building “but there will be many wounded people when it explodes.”

“I plan on remotely detonating the device as soon as there is a large police presence,” it ended.

By evening, almost expecting a threat

By the time the threat came to Cázares-Kelly’s office, she had heard about a few others and was almost expecting one. But she said she may have forgotten to relay the news of other similar threats to her colleague checking the email inbox.

Shortly after it was sent, the colleague walked into her office looking worried. He had printed it out, and his hand shook as he held the paper.

She quickly reached out to the head of building security, who was already aware of the threats to other counties. He then contacted police.

At that point, the office was pretty quiet. Ballots are counted in a different location by the elections staff, so her recorder’s office staff was just there to collect dropped off ballots from the drive-thru ballot drop box in front of the office.

She called her staff into a huddle to tell them about the threat. While she knew it was unlikely to be a real threat, she still said it was difficult for her, emotionally, to relay the message to her staff.

“You announce something like that, it’s very scary,” she said.

No staff members chose to leave. There are cameras and security personnel around the building, people have to go through security scans to enter, and all of their doors have key card entry. As soon as mail ballots are in the building, she said, staff is even more vigilant about tracking who is coming in and out.

Soon, a police dog was outside the building, sniffing the flowers and plants, and casing the parking garage. In the end, she said, she was glad she took the precautions she did.

“My biggest fear is, what if I don’t take this seriously, and it’s serious, and my staff gets hurt?”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.