Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Wisconsin’s free newsletter here.

Update, Sept. 17, 2024: A Dane County judge ruled against Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on Monday in his bid to get his name removed from the presidential ballot or covered with a sticker on each ballot. Now, Kennedy’s case is pending in a Waukesha County-based appeals court. Meanwhile, dozens of county clerks have already received printed ballots for the election, which municipal clerks must begin sending out by Sept. 19.

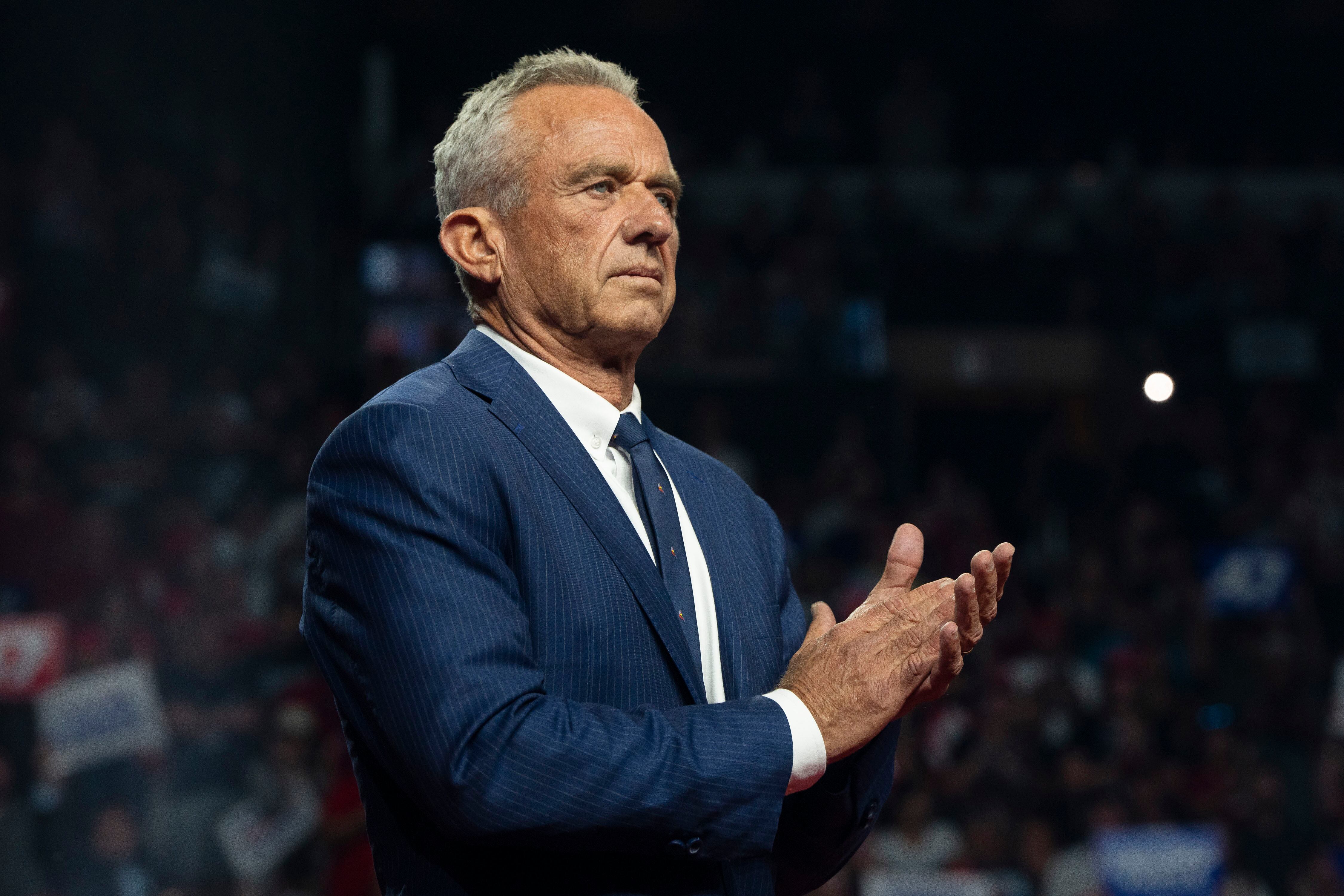

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is asking a court to remove his name as an independent presidential candidate from Wisconsin’s November ballot, after the state election commission rejected his request to be removed when it finalized the ballots last week.

A court victory for Kennedy would force clerks across Wisconsin who have already finalized their ballots to restart the time-consuming process.

Regardless of how the courts rule, the issue could fuel a legislative debate over whether to change a state law that appears to make it virtually impossible for candidates to get off the ballot once they file nomination papers and qualify to appear on it.

Kennedy’s lawsuit, filed against the Wisconsin Elections Commission in Dane County Circuit Court, follows similar legal action that he took in Michigan and North Carolina after those states’ election officials similarly rejected his efforts to withdraw from the ballot. The lawsuit in Michigan was swiftly rejected, while the North Carolina one is still pending.

Kennedy said on Aug. 23 that he was dropping out of the race and endorsing Republican nominee Donald Trump. He filed to withdraw his candidacy ahead of a Wisconsin Elections Commission meeting on Aug. 27 to give ballot access to presidential candidates. Five of the bipartisan agency’s six commissioners — three Democrats and two Republicans — approved putting him on the ballot despite his request to withdraw from it. One commissioner, Republican Bob Spindell, voted to remove him from the ballot.

They cited a law stating that candidates who file nomination papers and qualify to be listed on the ballot can’t decline nomination and must appear on the ballot unless they die.

The law troubled some of the commissioners, like Republican Don Millis, who said it would make sense to allow candidates to withdraw from the ballot up to the point that the commission sets the ballot. Still, Millis voted to keep Kennedy on the ballot.

When he announced his withdrawal, Kennedy said that being on the ballot in battleground states would benefit Democrats and that he would seek to get his name removed in those states. A Wisconsin-focused Marquette Law School Poll found Kennedy received more support from Republican voters than Democratic ones.

“Our polling consistently showed that by staying on the ballot in the battleground states, I would likely hand the election over to the Democrats, with whom I disagree on the most existential issues,” Kennedy said.

His lawsuit alleges that as an independent, he is being treated differently from major party candidates in a way that violates the First Amendment and a constitutional clause guaranteeing equal protection.

The complaint points to a state law allowing major party candidates to submit their presidential and vice presidential candidates up until the first Tuesday of September, while independent candidates have to file nomination papers by the first Tuesday in August.

Those different standards give major parties more time to vet candidates and decide their best course of action, Kennedy’s lawyers state.

The lawsuit further alleges that candidates don’t qualify to appear on the ballot until the Wisconsin Elections Commission approves them. Until that date, the lawsuit states, the commission should have allowed him to withdraw from the ballot.

“In First Amendment parlance: it has compelled him to not just speak, but to associate with a cause he doesn’t want to be part of,” the lawsuit states.

Wisconsin Elections Commission spokesperson Riley Vetterkind didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Legislative change may follow ballot access debate

Rep. Scott Krug, a Republican who chairs the Assembly Elections Committee, said he objects to the law that commissioners cited in keeping Kennedy on the ballot. He’s considering a proposal to change that law next legislative session.

“I have a hard time seeing why we want to force somebody to be on the ballot, even if they are seen by one side as trying to play shenanigans or whatever some have said that he’s trying to do,” Krug said. “It’s still somebody’s freedom to associate however they want to. And I just don’t see it being a good choice for good policy and long term good governance saying, ‘Hey, you’ve got to do it. We know you don’t want to but you have to.’”

Krug’s proposal, which he has yet to solidify and circulate, would allow independent candidates to withdraw from the ballot anytime before the governing board overseeing ballot access finalizes its list of candidates.

“If you’re in the process of being approved for ballot access as an individual candidate who went through nomination papers, why not let you off? What are we hurting by letting you go?” Krug said.

The criticism against such a law, Krug said, is that it would incentivize coalition-building — allowing independent candidates to drop off the ballot at the last minute, in exchange for something, to give other candidates a boost.

But Krug said European politics has long operated through coalition-building.

It’s unclear how much support the proposal could receive in the Legislature. Lawmakers are expecting Republicans’ near-supermajority to shrink substantially after the November election, with some Democratic legislative leaders even predicting they’ll flip the Assembly to a Democratic majority.

Candidates who no longer wanted to appear on the ballot used to have an easier off-ramp.

A state law on the books until the late 1970s allowed a candidate to “decline the nomination by delivering to his filing official a written, signed and acknowledged declination,” according to the Legislative Reference Bureau.

The drafting file for the legislation that repealed that law didn’t offer insight into why lawmakers wanted to change it, the bureau stated.

Clerks have sent ballots to the printer

Late, unexpected changes to the ballot can create major logistical difficulties for election planning. Clerks have to send their first ballots out to absentee voters in just two weeks.

Clerks typically finalize ballots well before they go out to voters. If a candidate seeks to withdraw after that point — Kennedy’s lawsuit was filed a week after the commission approved putting him on the ballot — a successful request could force clerks to redesign and reprint ballots.

A Dane County election official said the lawsuit was filed after the county already sent finalized ballots to the printer. La Crosse County Clerk Ginny Dankmeyer, a Democrat, said many other clerks around the state have finalized their ballots as well, “and printers are already printing.”

Dankmeyer said she waited a few days after the election commission finalized presidential candidates before she finalized ballots and sent them to be printed, just in case a lawsuit came up.

“I actually waited until Friday to send my ballots out, just because I figured that would be the three days if someone would file a lawsuit, that they would do it right away,” she said. “And then someone waited until … a week later to file a lawsuit.”

If the lawsuit is successful, Dankmeyer said, “there’s a lot involved. There’s a cost involved. There’s time involved. There’s confusion. If these ballots get back and get mailed out before a decision is made, then a new ballot has to be mailed.”

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.